Forests

Browse our research

Tell me about...

forests

Our forests are a valuable public good. In Saugeen-Bruce, forests are home to not only a wide variety of tree species, but also unique wildlife habitats. They are home to areas of rare, threatened, or endangered plants and animals, including the Eastern Massassauga Rattlesnake, the American chestnut (previously devasted by chestnut blight, which killed between 3 and 4 billion trees in the first half of the 20th century), and numerous wildflowers.

Forests are places we can go to enjoy and explore nature, through hiking, camping, mountain biking, cross-country skiing, and more. Forests provide us with food, shelter, fuel, and supplies that enhance our daily lives, including medicinal ingredients, lumber for buildings, paper, and more.

Forests also play an important role in balancing the Earth’s supply of carbon dioxide.

Seeing the forest for the trees

Forests have trees, of course. But how many trees make a forest? And how big must they be?

According to the Government of Canada, forests are lands having a minimum tree crown cover of 25%, minimum land area of one hectare, and a minimum tree height of five metres. [70]

This also includes areas that have the potential to reach these thresholds, such as recently burned or harvested areas where new trees are not yet five metres tall. This doesn’t include open grasslands with occasional trees or trees planted in urban lots and medians.

Photo Credit: Laila Goubran

History of forests in Saugeen-Bruce

Prior to the colonization of the Saugeen-Bruce area by non-Indigenous settlers, extensive forests covered much of the land.

The Saugeen Conservation Forest Management Plan describes the history

of the area:

“These forests were predominately hardwoods with some dense cedar swamps. This type of forest cover hindered the growth of agricultural crops and was removed across a large portion of the watershed. By the early 1880s these once forested areas were reduced to the farm woodlots which can be observed today.

“Most of the Greenock Swamp, the Osprey Wetlands, and other smaller wetlands, were never cleared due to excessive soil moisture. Much of the cleared land had proven to be marginal farm land and was later abandoned or removed from farming. A small fraction of this land has since been returned to forest cover." [33]

Greenock swamp logging camp crew

Photo credit: brucemuseum.pastperfectonline.com

The Bruce County Forest Management Plan shares a similar story:

“The Sauble Beach area had all the trees removed during homesteading but the resulting fields proved to be no match for the natural elements. The sandy soils began to move with the winds. This led to a near desert condition.

“Beginning in 1938 some properties were purchased by the County. Trees were once again reinstated on these open areas and the process of soil stabilization began to take place with the results becoming apparent after only a few years.” [35]

Logs likely being taken out of the Greenock swamp bordering on Glammis.

Photo credit: brucemuseum.pastperfectonline.com

Often, forests were harvested by selecting only the large, healthy, and most valuable trees. This process, known as “highgrading,” left the remaining forests with only poor-quality trees.

Current good forestry practices no longer permit highgrading. Sustainable harvesting now attempts to ensure that forests will remain healthy for generations to come. Some of these practices include limits on the diameter of trees that can be cut down.

Limits on harvesting are part of the broader scope of forest management: the process of planning and implementing practices for stewardship and use of the forest aimed at fulfilling relevant ecological (including biological diversity), economic, and social functions of the forest in a sustainable manner.

Most of the forests in the Saugeen-Bruce region are managed by the government, counties, or conservation authorities.

How forests fight climate change

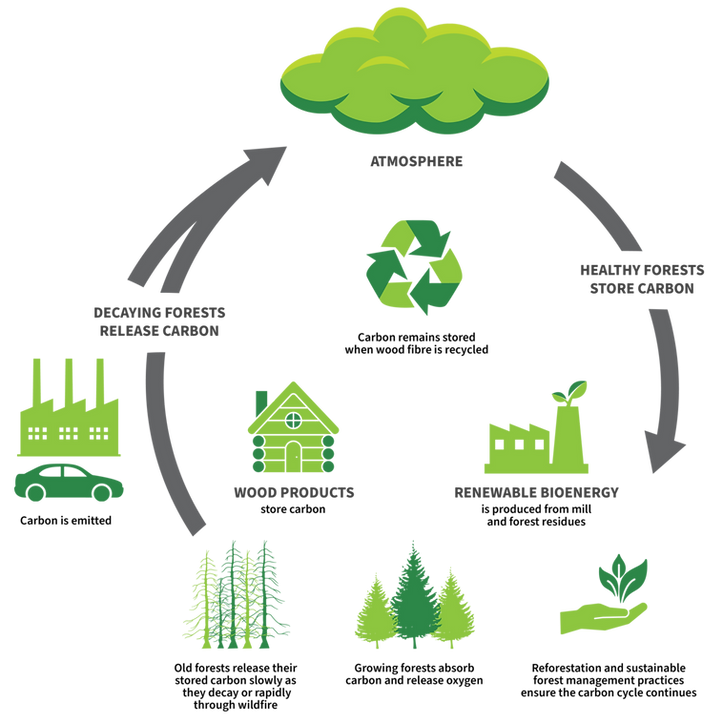

Forests—including the trees, plants and soil—are terrific carbon sinks.

Trees and other forest vegetation store carbon through photosynthesis. They absorb carbon dioxide from the air, then break it down into carbon and oxygen. The oxygen is released back into the air, while the carbon is stored in leaves, stems, roots, and flowers.

Trees are particularly good at storing carbon because they are about 50% carbon, live for a long time, and take a long time to rot (particularly in cooler climates, like Ontario). [36]

While forests can be a valuable tool in sequestering carbon, they are also increasingly vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Threats include loss of productive forest area, deficits in regeneration, and increased risk of fire and insect outbreak. [37]

When forests are destroyed, we not only lose their ability to remove excess carbon from the atmosphere—we also gain the carbon that they had been storing already.

Sustainable Forest Management and Carbon Storage

An Ontario boreal forest example with wildfire suppression

Changing climate, changing forests

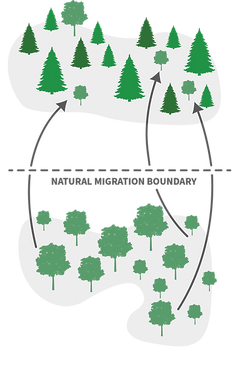

Forests on the move

Trees are expected to generally migrate to higher latitudes as temperatures rise and areas that used to be too cold for certain tree species become more hospitable. According to the ELPC, there is strong evidence that forest ecosystems are already responding to climate change in the Great Lakes region. Some studies have shown that individual tree species are moving northward and westward at a rate of 10-15 kilometers per decade. [39]

An important question is whether the climate will change faster than tree species are able to migrate, which could cause certain species to go extinct, or convert forests into grasslands. [40] Forests are more fragmented than they have been in the past, which may hinder the ability of trees to shift as the temperature changes.

Assisted migration is a climate change adaptation strategy that involves the human-assisted movement of trees and plants to more climatically suitable habitats. [41] Assisted migration may be able to prevent certain tree species from going extinct and may alleviate some of the risks that climate change poses to forest biodiversity. [42]

However, there are also possible risks, including unforeseen impacts of a new species on the hosting environment, a species becoming invasive, or investment loss if the population does not adapt to new local conditions.

Natural Resources Canada describes three kinds of human-assisted migration:

Assisted

population migration

(lower risk)

The movement of populations within a species’ established range.

Assisted range expansion

(intermediate risk)

The movement of species to areas just outside their established range, facilitating or mimicking natural range expansion.

Assisted long-distance migration

(higher risk)

The movement of species to areas far outside their established range (beyond areas accessible through natural dispersal).

Research into assisted migration is ongoing. The Forest Gene Conservation Association (FGCA) is a not-for-profit organization whose mission is to ensure that genetic diversity is recognized and protected as the foundation of a resilient forested landscape. [43]

They work with partners in Ontario to establish assisted migration trials to monitor the performance of species sourced locally and from southern sources based on predicted climate change analysis. [44]

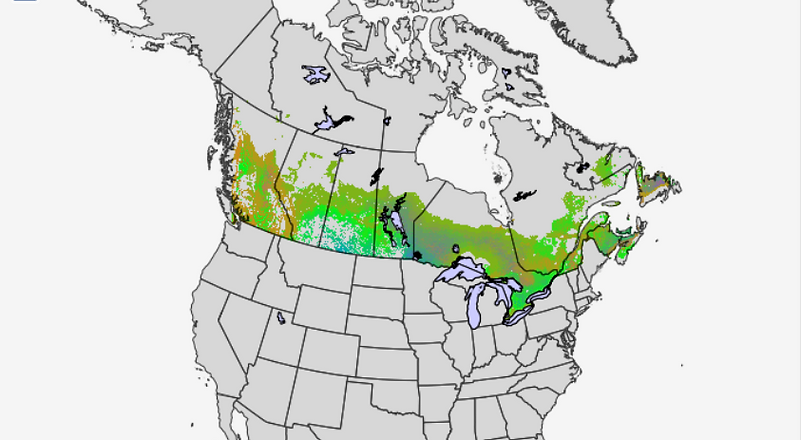

Forest Vulnerability Assessment Tool

Vulnerability of trees species to climate change

Natural Resources Canada

Ripple effects of water

Increasing carbon dioxide levels are changing the way forests use water

Extreme weather events, such as intense storms or periods of drought, can have huge effects on Ontario forests. [45] Some effects, like direct damage to trees from an extreme storm, are immediate. Others are more subtle or difficult to predict.

The climate promises to affect insect populations, and some insects that are relatively harmless now may become severely disruptive in the future. Trees that are stressed by drought will have fewer reserves to battle insect and disease damage.

The amount of carbon in the atmosphere also influences how forests use water. Plants remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere through photosynthesis, a process that is accompanied by the loss of water vapour from their leaves. The ratio of how much water is lost compared to how much carbon is gained is known as water-use efficiency.

One study has shown that temperate and boreal forests in the Northern Hemisphere have increased their water-use efficiency from 1993-2013. [46]

As carbon dioxide levels increase, forest ecosystems will change the way they use water. This could cause ripple effects across the landscape, since water use is tied to land use, land cover and other hydrologic responses. How these systems work together and feed back onto each other is an area of ongoing study. [47]

Invasive species

When non-native species increase their reach, they can cause great harm to an ecosystem

Effects of climate change on invasive species include:

More frequent extreme weather events can stress native species and create opportunities for invasive species movement.

Climate affects the life cycles of pests and their ability to spread into new areas.

Increased carbon dioxide uptake in plants can increase herbicide resistance.

Some invasive species, like the spongy moth, are controlled by diseases that can be less effective in warm and dry conditions.

Invasive insects can pose a dire threat to both forests and urban trees. Take, for example, the emerald ash borer. The beetle’s larvae tunnel under the ash tree bark, cutting off the tree’s supply of nutrients and water. The emerald ash borer has devastated millions of ash trees in North America and is the costliest invasive species in Ontario. [48] Up to 99% of all ash trees are killed within 8-10 years once the beetle arrives in an area. [49]

Adapting to new invasive species threats requires an understanding of which species may arrive, how the trees may respond, and how forest management practices can mitigate the impacts. The best way to save trees is to prevent invasives from arriving in the first place. Diversifying forests, including urban forests, can help reduce the number of trees that are vulnerable to a particular invasive species. [50]

Species at Risk

More than 200 species of plants and animals are at risk of disappearing from Ontario.

The Endangered Species Act provides a way of assessing species at risk and providing protection for the species and their habitats.

Extinct:

A species that no longer exists anywhere in the world

Extirpated:

A species that no longer exists in the wild in Ontario, but lives somewhere else in the world

Endangered:

A species that is facing extinction or extirpation in Ontario

Threatened:

A species that is not currently endangered, but is likely to become endangered if threatening factors are not addressed

Special Concern:

A species with characteristics that make it particularly sensitive to identified threats

In early 2023, Ontario added seven animals to its list of species at risk.

SPECIES AT RISK IN OUR REGION

.png)

.png)

.png)